Languages and Automata

13 Nov 2018 | theorySome notes for CS 181. This is about context-free grammars, pushdown automata, the pumping lemma for context-free grammars, and closure properties of context-free language. I also just added in notes for Turing machines.

Context-Free Grammars

A context-free grammar is represented by a tuple $( V, \Sigma, R, S)$ where

- $V$ is the set of all variables

- $\Sigma$ is the alphabet

- $R$ are all the derivation rules (i.e. $S \rightarrow aSb \mid \epsilon$)

- $S$ is the start variable

At each step in time, you can replace one of the variables with one of it’s derivations. The language of a grammar is the set of all strings that can be derived. Context free grammars are widely used, for example, one could construct a CFG that accepts a language iff it has the proper syntax (as in the case for some programming languages).

Example grammars and their languages

-

\(S \rightarrow AA \\ A \rightarrow A\) This CFG is invalid, as there are no terminal symbols, so $L = \emptyset$

-

\(S \rightarrow aSa \mid aBa \\ B \rightarrow Bb \mid b\) For this CFG, $L = \{a^nb^+a^n, n \geq 1\}$.

-

\(S \rightarrow abS \mid a\) For this CFG, $L = \{(ab)^*a\}$.

-

\(S \rightarrow aSa \mid B \\ B \rightarrow bB \mid \epsilon\) For this CFG, $L = \{a^nb^*a^n, n \geq 0 \}$.

-

\(S \rightarrow SS \mid aS \mid b\) For this CFG, $L = \{(\Sigma)^*b\}$.

-

\(S \rightarrow AB \\ A \rightarrow aAa \mid \epsilon \\ B \rightarrow bBb \mid \epsilon\) For this CFG, $L = \{ (aa)^* (bb)^* \} $.

Constructing a grammar for a language

-

$L = \{ a^n (a \cup b)^n, n \geq 0 \}$ is defined by the CFG: \(S \rightarrow aST \mid \epsilon \\ T \rightarrow a \mid b\)

-

$L = \{ w : w = w^R \}$ is defined by the CFG: \(S \rightarrow aSa \mid bSb \mid b \mid a \mid \epsilon\)

-

$L = \{ (a \cup b)^n a (a \cup b)^n, n \geq 0 \}$ is defined by the CFG: \(S \rightarrow TST \mid a \\ T \rightarrow a \mid b\)

-

$L = \{ w : w \text{ contains } baa \}$ is defined by the CFG: \(S \rightarrow TbaaT \\ T \gets aT \mid bT \mid \epsilon\)

-

$L = \{ a^nb^m, n \geq m \}$ is defined by the CFG: \(S \rightarrow aSb \mid aS \mid \epsilon\)

-

$L = \{ a^nb^m, n > m \}$ is defined by the CFG: \(S \rightarrow aSb \mid aS \mid a\)

-

$L = \{ a^nb^m, 0 \leq m \leq 3n \}$ is defined by the CFG: \(S \rightarrow aSBBB \mid \epsilon \\ B \rightarrow b \mid \epsilon\)

-

$L = \{ w : w \text{ contains more than 3 } a \}$ is defined by the CFG: \(S \rightarrow TaTaTaT \\T \rightarrow aT \mid bT \mid \epsilon\)

-

$L = \{ a^nb^nb^ma^m, n,m \geq 0 \}$ is defined by the CFG: \(S \rightarrow UR \\ U \rightarrow aUb \mid \epsilon \\ R \rightarrow bRa \mid \epsilon\)

-

$L = \{ \Sigma (a \cup b)^n a (a \cup b )^n, n \geq 0 \}$ is defined by the CFG: \(S \gets TR \\ T \gets a \mid b \\ R \gets TRT \mid a\)

Key things to note here: try to break down the CFG into smaller, simpler parts and then try to compose these parts in order to get a solution for the language. Some key building blocks to keep in mind are examples 3 and 5.

Ambiguity

A grammar is ambiguous if some string has multiple distinct parse trees. A common source of ambiguity is empty strings, or $\epsilon$.

For example, the CFG \(S \rightarrow R \mid T \\ R \rightarrow aRb \mid \epsilon \\ T \rightarrow aT \mid \epsilon\) is ambiguous, as the string $\epsilon$ can be parsed either using $T$ or $R$.

Converting an ambiguous grammar into a non-ambiguous grammar

-

\(S \rightarrow ABAB \\ A \rightarrow aA \mid \epsilon \\ B \rightarrow bB \mid \epsilon\) is ambiguous for the string $ab$.

A non-ambiguous grammar is given by \(S \rightarrow ABAB \mid BAB \mid ABA \mid BA \mid AB \mid A \mid B \mid \epsilon \\ A \rightarrow aA \mid a \\ B \rightarrow bB \mid b\)

-

\(S \rightarrow aSb \mid aaSb \mid \epsilon\) is ambiguous for the string $aaabb$.

A non-ambiguous grammar is given by \(S \rightarrow aSb \mid R \\ R \rightarrow aaRb \mid \epsilon\). This imposes an ordering so we expand $ab$ before we expand using $aab$.

-

\(P \rightarrow PP \mid aPb \mid ab\) is ambiguous for the string $ababab$.

A non-ambiguous grammar is given by \(P \rightarrow ab \mid aPb \mid abP \mid aPbP\). Note: This is the language of all properly nested parenthesis. We make it non-ambiguous by anchoring on open parenthesis.

Designing unambiguous grammars

- Design an unambiguous grammar for $L = \{w : w \text{ has at least as many } a \text{ as } b \}$.

We can use the unambiguous language designed in 3, but just consider the other case where the parenthesis may be switched. \(S \rightarrow S^{'}\mid S^{''} \mid \epsilon \\ S^{'} \rightarrow P S^{''} \mid P \\ S^{''} \rightarrow Q S^{'} \mid Q \\ P \rightarrow ab \mid aPb \mid abP \mid aPbP \\ Q \rightarrow ba \mid bQa \mid baQ \mid bQaQ\)

Pushdown Automata

Pushdown automata can be thought of as an extension to normal NFA/DFA. However, the automata now has access to a stack (FIFO), and each transition is of the from $\alpha, \beta \rightarrow \gamma$.

- $\alpha$ is character that needs to be read to make the transition.

- $\beta$ is character that needs to be popped from the stack ($\epsilon$ means don’t pop anything).

- $\gamma$ is character that needs to be pushed onto the stack ($\epsilon$ means don’t push anything).

A pushdown automata is then represented by the tuple $(Q, \Sigma, \Gamma, \delta, q_0, F)$ where

- $Q$ is the set of all states

- $\Sigma$ is the input alphabet

- $\Gamma$ is the stack alphabet

- $\delta$ is the transition function. $\delta : Q \times (\Sigma \cup \{\epsilon\}) \times (\Gamma \cup \{\epsilon \}) \rightarrow Q$

- $q_0$ is the start state $q_0 \in Q$

- $F$ is the set of accept states $F \subseteq Q$

Every language that has a context-free grammar can be written as a PDA, and vice versa.

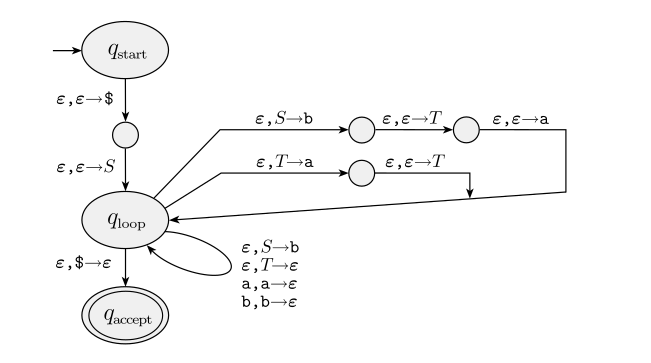

To do this, given a CFG described by $(V, \Sigma, S, R)$, we can construct a corresponding PDA $(\{q_{start}, q_{loop}, q_{accept}, \} \cup E, \Sigma, \Sigma \cup V \cup \{ \epsilon \}, \delta, q_{start}, \{q_{accept}\})$ where $\delta$ is defined so that.

- $\delta(q_{start}, \epsilon, \epsilon) = (q_{loop}, S \perp)$

- $\forall \text{ variables } S \text{ and their respective derivation } w . \delta(q_{loop}, \epsilon, S) = (q_{loop}, w)$

- $\forall \text{ terminals } t . \delta(q_{loop}, t, t) = (q_{loop}, \epsilon)$

- $\delta(q_{loop}, \epsilon, \perp) = (q_{accept}, \epsilon)$

To go from a PDA to a grammar, we first have to clean up the PDA. We do this by first enforcing a unique accept state, by adding $\epsilon$ transitions from each accept state in the PDA to a new accept state outside of the PDA.

Next, we ensure that the PDA empties it’s stack before accepting, by adding in $\perp$ to $\Gamma$ and add in a state with a loop that will dump the stack before accepting.

Finally we modify all the $\delta$ transitions so that each transition is either a push or a pop. This is easy to do - if our $\delta$ transition is all $\epsilon$ we can just expand it, otherwise we can split them.

If $L$ is recognized by a PDA given by $(Q, \Sigma, \Gamma, \delta, q_0, F)$ then $L$ is a CFG with the following rules:

- $\forall_{q \in Q} . V_{q,q} \rightarrow \epsilon $

- $\forall_{p, q, r \in Q} . V_{p, q} \rightarrow V_{p, r} V_{r, q} $

- $\forall_{p, q, r \in Q} \forall_{\sigma, \tau \in \Sigma_\epsilon } \forall_{\gamma \in \Gamma} \mid \delta(p, \sigma, \epsilon) \ni (r, \gamma), \delta(s, \tau, \gamma) \ni (q, \epsilon) . V_{p, q} \rightarrow \sigma V_{r, s} \tau$

More specifically, for $p, q \in Q$ $L_{p,q} = \{ w : w \text{ can take the PDA from } p \text{ w/ empty stack to } q \text{ w/ empty stack }\}$. Thus $L_{PDA} = L_{q_{start} q_{final}}$

With this in mind, we can say that language $L$ is context-free if it has a context-free grammar of a PDA. It’s also easy to see that every regular language has a context-free grammar.

Pumping Lemma for Context-Free Languages

Context-free languages have a pumping lemma, similar to regular languages.

\[L \text{ is a CFL } \implies \exists p . \forall s \in L \text{ s.t. } \vert{s}\vert \geq p . \exists u v x y z \text{ s.t. } s = uvxyz, \vert{vxy}\vert \leq p, \vert{v}\vert + \vert{y}\vert \neq 0 . \forall i . uv^ixy^iz \in L\]To prove that a language is not context free, we will use the contrapositive of the pumping lemma.

\[\forall p . \exists s \in L \text{ s.t. } \vert{s}\vert \geq p . \forall u v x y z \text{ s.t. } s = uvxyz, \vert{vxy}\vert \leq p, \vert{v}\vert + \vert{y}\vert \neq 0 . \exists i . uv^ixy^iz \notin L \implies L \text{ is not a CFL}\]Examples

-

$L = \{ a^nb^nc^n : n \geq 0\}$

Let $p$ be arbitrary, and $s = a^pb^pc^p$. For any valid decomposition, $uxz \notin L$, as we have to be removing a character, but it is impossible for us to remove one of each, as $\vert{vxy}\vert \leq p$, so it can span at most one transition, either from $a$ to $b$ or $b$ to $c$. Therefore $L$ is not a CFL.

Proof of Pumping Lemma

TODO: This is a bit involved, so skipping this for now.

Closure Properties

- CFLs are closed under union.

- CFLs are closed under concatenation.

- CFLs are not closed under intersection.

- CFLS are not closed under complement.

- CFLs are closed under Kleene star.

- CFLs are closed under reversal.

Turing Machines

Conceptually a Turing machine acts on an infintely long tape, on which the input is written. While the tape has no right hand side, it has a distinct left hand side. The Turing machine, at each step, can read from the tape, but also write to the tape, and then move the head left or right.

A Turing machine $M$ is represented by the tuple $(Q, \Sigma, \Gamma, \delta, q_0, q_{accept}, q_{reject})$ where

- $Q$ is a set of states

- $\Sigma$ is the alphabet

- $\Gamma$ is the tape alphabet

- $\delta$ is the transition function $\delta : Q \times \Gamma \rightarrow Q \times \Gamma \times \{ L, R \}$

- $q_0$ is the start state

- $q_{accept}$ is the accept state

- $q_{reject}$ is the reject state

When $M$ reaches either $q_{accept}$ or $q_{reject}$ respectively, it halts and either accepts/rejects the string. It is possible that $M$ never enters either state, which we consider rejection by default.

Sample problems and solutions for Turing machines.

- Create a Turing machine that recognizes $L = \{ w \text{#} w \} $

Leave a dot at the first character.

2) Scan to the right until your find a #, and dot that.

3) Read left until you reach a dotted character (back at start now)

4) remember this value (finite b/c \Gamma is finite) (let's call it x)

5) then undot and read right. dot this character

6) then read right until you reach another dotted character.

7) if this character is different from x, reject otherwise

undot that character and then go right and dot that character if it exists. if it is empty, then accept if the other dot is at #, otherwise reject.

- Create a Turing machine that recognizes $L = \{ 0^{2^n} : n \geq 0 \} $

Go through the input and dot every other 0 in the string. If we run into the end of the string before this is possible, then reject the string.

Repeat this until all 0s are dotted, at which point accept the string.

- Create a Turing machine that recognizes $L = \{ w_1 \text{#} w_2 \ldots \text{#} w_n : w_i \neq w_j \forall i, j, i \neq j\}$

Leave a dot at the first character

Scan to the right for the next # and dot that. repeat this until there are no more #

Compare the dotted characters, if they are equal then reject otherwise move the dot to the next #

Put the R/W head immediately after the last dotted string, then go to 1

Completeness of Turing machines

Church-Turing thesis - The Turing machine is a universal model of computation. Any real world computation can be simulated by a Turing machine.

More specifically, if $L$ is recognized by some computational model/device then that language is Turing recognizable. This is not proven, it’s merely just a conjecture.

A couple example reductions

- $L$ is recognizable by a Turing machine with a bidirectional tape it is Turing recognizable.

Take the left hand side of the tape and interleave it with the right hand size such that each element of the tape is now a 2-tuple.

- $L$ is recognized by a Turing machine with $k$ tapes and $k$ head, then L is Turing recognizable.

To simulate one-step of the $k$-tape Turing machine, scan the tape, memorizing the $k$ circled symbols, and then scan again, updating the circled symbols and shifting the actual circles.

- $L$ is recognized by a nondeterministic Turing machine $\iff$ $L$ is Turing-recognizable.

Try out all legal sequences of moves in lexicographical order and accept if some sequence accepts.

Create 3 tapes, the input tape, sequence tape and work tape.

Initialize the empty sequence tape, Increment the sequence Initialize the work tape to the input string Apply sequence to work tape, one step at a time. If you reach $Q_{accept}$ then accept. Return to step 2.

- $L$ is recognized by a $k$-stack automata $\iff$ $L$ is Turing recognizable.

Use k-tape Turing machine, gives a nondeterministic Turing machine. Use Turing machine as concatenation of two stacks.

left move - pop stack 1 and push stack 2, vice versa for right move.

Decidability

A Turing machine $M$ decides a language $L$ if:

- $M$ recognizes $L$.

- $M$ halts on every input.

A language $L$ is decidable $L$ and $\bar{L}$ are Turing recognizable. Then given Turing machine $M$ that recognizes $L$ and $M’$ that recognizes $\bar{L}$, we construct a decider for $L$ by running $M$ and $M’$ simultaneously on the input and returns whatever answers first.

Decidability of DFAs

We can also consider an encoding of DFAs to a binary string. This allows us to interpret strings as DFAs and vice-versa. Let’s consider a couple of interesting languages.

NOTE: This is pretty important so make sure you have it down.

- $ \{ \langle D \rangle : \text{D is a DFA s.t. } L(D) \neq \emptyset \} $

reject if encoding is invalid write all vertices out on a seprate tape mark each vertex if there is an edge repeat until there are no unmarked edges. for every marked vertex, mark all neighbors of V Accept if all vertices of E are marked, reject otherwise. - Show that $L = \{ \langle D, w \rangle : \text{ D is a DFA that accepts w} \}$ is decidable.

To determine whether input $D, w$ is the language, Firstly, we construct a DFA that only recognizes $w$, denoted by $W$. Note that since this language is finite, it must be regular. Since regular languages are closed under intersection, we can check whether $D’ = D \cup W$ is empty, by checking if $L(D’) \eq \emptyset$.

- Show that $L = \{ \langle D, D’ \rangle : L(D’) = L(D’’) \}$ is decidable.

Note that $(L(D’) \setminus L(D’’)) \cup (L(D’’) \setminus L(D’))$ is a regular language under closure properties, so it can be represented by a DFA $D$

Now we can just check if $L(D)$ is empty, using our language emptiness checker.

-

Show that $L = \{ \langle D \rangle : \text{D accepts a string of even length} \}$

-

Show that $L = \{ \langle R, S \rangle : L(R) \subset L(S) \}$ is decidable where $R, S$ are regular expressions.

-

Show that $L = \{ \langle D \rangle : \text{ D is a DFA that accepts w and it’s reverse} \} $ is decidable.

-

Show that $L = \{ \langle D \rangle : \vert L(D) \vert = \inf \} $ is decidable.

If the DFA accepts a string greater than $k$, it will accept an infinite number by the pumping lemma.

Decidability of CFGs

Theorem: Given CFG $G$, if $L(G) = \emptyset$ then some string $w \in L(G)$ has a parse tree of depth $d \leq \vert V \vert$.

Proof: Let $P$ be the smallest parse tree for $G$.

If depth $P > \vert V \vert$ then some path must repeat a variable $v$ by PHP. Let $A$ be the parse tree for the first occurrence of $v$ and $A’$ be the parse tree for the second occurrence.

Then I could generate a smaller parse tree by replacing $A$ with $A’$. This is a contradiction since $P$ is the smallest parse tree for $G$. Therefore depth $P \leq \vert V \vert$.

- Show that $L = \{ \langle G \rangle : L(G) = \emptyset \}$ is decidable.

To do this we will try out all candidate parse trees of depth $\leq \vert V \vert$.

- Show that $L = \{ \langle G, w \rangle : \text{G is a CFG that generates w} \}$ is decidable.

Notice that the language $L_w = \{ w \}$ is regular, as it is finite, so $L(G) \cup L_w$ is a CFG. We know from above that this CFG is decidable, so therefore, so is $L$.

- Show that $L = \{ \langle p \rangle : \text{ p is a PDA that accepts infinitely many strings} \}$

$p$ accepts infinitely many strings if it accepts any string that is greater than $k$, or the pumping length. We can construct the regular language, $L_k = \{ w : \vert w \vert > k \}$. Then, we just simply have to convert $p$ into a grammar, and then check $L(p) \cup L_k$ is empty, which is decidable.

- Show that $L = \{ \langle p \rangle : \text{ p has no unreachable states }\}$

For all states, make that state into an accept state, and check if the CFG for the new PDA is empty or not.

Undecidability

Cantor’s argument for the existence of an unrecognizable language - set of all languages is uncountable, but the set of all Turing machines is countable (since every Turing machine can be written as a binary string, and the set of all binary strings is countable). Therefore there must be some languages that are not recognized by a Turing machine.

Consider the language $L_{unrec} = \{ w : w \notin L(M_w) \}$, which is the set of all strings, such that the string is not in the language of the Turing machine representation of the string.

This language is not recognizable.

Halting problem - consider the language $HALT = \{ \langle M, w \rangle : \text{ M is a turing machien that halts on w } \}$

We know that $L_{unrec} = \{ w : W \notin L(M_w) \}$ is unrecognizable and therefore undecidable. However, suppose $HALT$ was decidable. Then for input $x$ we can see that $\langle M_x, x \rangle \notin HALT \implies x \in L_{unrec}$, while $ \langle M_x,s \rangle \in HALT \implies x \notin L_{unrec}$. This means that if $HALT$ is decidable, so would $L_{unrec}$, which is a contradiction. Therefore $HALT$ is undecidable.

Note that although $HALT$ is undecidable, it is recognizable. $\bar{HALT}$ is therefore not recognizable.

Rice’s Theorem: Any nontrivial property about the language recognized by a Turing machine is undecidable.

A property is said to be nontrivial if some Turing machine has it and some Turing machine doesn’t have it.

For example, consider $L= \{ \langle M \rangle : \text{ M is a Turing machine that halts on } \epsilon \}$

Clearly there is a Turing machine that halts on $\epsilon$ and a Turing machine that doesn’t halt on $\epsilon$ (runs forever). Therefore by Rice’s theorem, $L$ is undecidable.