Implementing DistBelief

08 Aug 2018 | machine-learning systems optimizationOver the past couple months, I’ve been working with Rohan Varma on a PyTorch implementation of DistBelief.

DistBelief is a Google paper that describes how to train models in a distributed fashion. In particular, we were interested in implementing a distributed optimization method, DownpourSGD. This is an overview of our implementation, along with some problems we faced along our way.

Please check out the code here!

Update: Our project is now on PyPi! You can install our code by running pip install pytorch-distbelief.

A brief introduction to Distbelief

For some context, I’m going to briefly explain DistBelief. You can check out the original paper here. Distbelief describes an entire framework for parallelizing neural networks, but we focused on the primary concept of the paper - two distributed optimization methods, DownpourSGD and SandblasterLBFGS.

We only implemented DownpourSGD, which is much simpler.

Downpour SGD

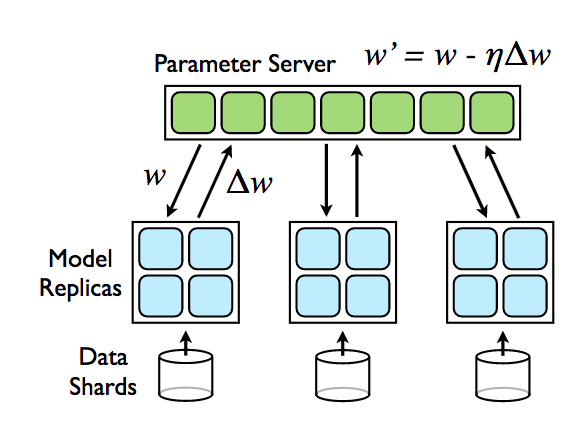

In DownpourSGD, there are two core concepts - a parameter server and a training node.

The parameter server is just a copy of the model parameters, which can send model parameters when requested and can also receive an accumulated gradient, which it then applies to its own copy of the parameters.

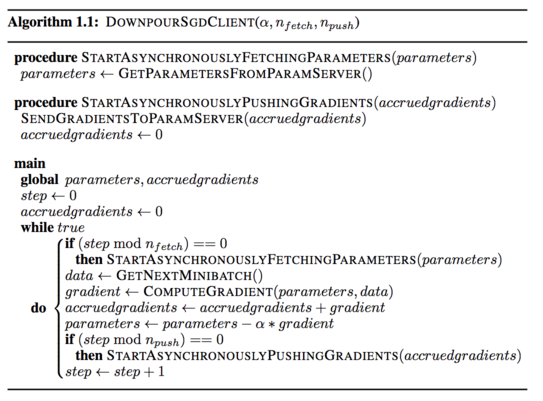

Downpour SGD is very similar to normal SGD, with two main exceptions.

- Before the training step, the training node asynchronously pulls the parameters from the parameter server. We do this every \(N_{pull}\) times.

- After we’ve applied our gradient update, we also accumulate it in another tensor. Once we sum \(N_{push}\) gradients, we send this accumulated gradient to the parameter server, and zero the accumulated gradients.

In both cases, we push/pull data asynchronously, so training continues as usual (forward pass, compute loss, backprop, apply gradient update) while we’re sending data.

The paper provides some pseudocode for the DownpourSGD client.

Starting off

We did some cursory research, and found a couple of great articles and tutorials.

- Akka implementation of DistBelief

- PyTorch distributed computing tutorial

- gevent actor model tutorial

Originally our plan was to use the gevent actor model to implement DistBelief. However, we quickly realized that the way we had envisioned it, we would need the training node to both pull gradients and also run the training step at the same time, while accessing some shared memory.

This is a big problem, because everything inside an actor is supposed to happen sequentially – which meant we couldn’t do asynchronous operations within an actor. What’s worse – if we separated these two steps into two different actors, we would have to send large amounts of data back and forth, increasing our communication overhead.

We figured an easier system would be to relax our system, so, instead of implementing DistBelief purely with actors, we build a more generic message passing system. Our implementation breaks one of the cardinal rules of the actor model, which is to never share state between actors.

Our idea was to first build a simple message passing system, and then implement a series of message listeners, with which we could implement DistBelief.

Sending Messages

We both had some experience with PyTorch, so figured we could use PyTorch’s distributed send and recv commands (along with their async counterparts, isend and irecv) to build a system to pass around gradients/parameters data.

Using this also provided some key advantages:

- Faster messaging interface, with support for Gloo and OpenMPI, not just TCP.

- Switching between messaging backends would be much much simpler.

- Avoid costly serialization. This isn’t entirely true, as I’m sure the message is serialized – but we were avoiding doing it in Python.

- Better integration with PyTorch. We wanted something that was simple to use, so we figured implementing it as a PyTorch optimizer would be the easiest.

However, we realized that we needed to not only send tensor data, but also some metadata with our message. This metadata would be easy to add in a JSON for example, but adding it into a tensor required a bit more thought.

Tensors as messages

Firstly, we realized that we couldn’t send a message for each parameter group, as we needed to have a set size for our message in order to use recv properly.

Therefore we needed to squash the parameters to a single parameter vector. It’s important to note that the gradients for a backward pass are also the same size as this single parameter vector. We also implemented a method to unsquash our model params. This takes in a single parameter vector, and a reference to the model, and unpacks each parameter into the appropriate model parameter group. This code allowed us to serialize any model into a singular tensor.

This tensor is the payload of our message. When we send this message, we prepend two extra elements. Element 0 is a MessageCode, which describes the intended message action, while element 1 is the rank (ID) of the sender.

Our message length is thus a tensor of size \(N_{params} + 2\).

Next we implemented a base class that described a MessageListener (similar to an event loop), as well a utility function to make sending a message easier.

class MessageListener(Thread):

"""MessageListener

base class for message listeners, extends pythons threading Thread

"""

def __init__(self, model):

_LOGGER.info("Setting m_parameter")

self.m_parameter = torch.zeros(ravel_model_params(model).numel() + 2)

super(MessageListener, self).__init__()

# for user to override

def receive(self, sender, message_code, parameter):

raise NotImplementedError()

def run(self):

_LOGGER.info("Started Running!")

self.running = True

while self.running:

_LOGGER.info("Polling for message...")

dist.recv(tensor=self.m_parameter)

self.receive(int(self.m_parameter[0].item()),

MessageCode(self.m_parameter[1].item()),

self.m_parameter[2:])

By extending receive, we could implement both our parameter server and our DownpourSGD client.

Defining our messages and handlers

With this in mind, we sketched out the different messages that the corresponding handlers would send/process.

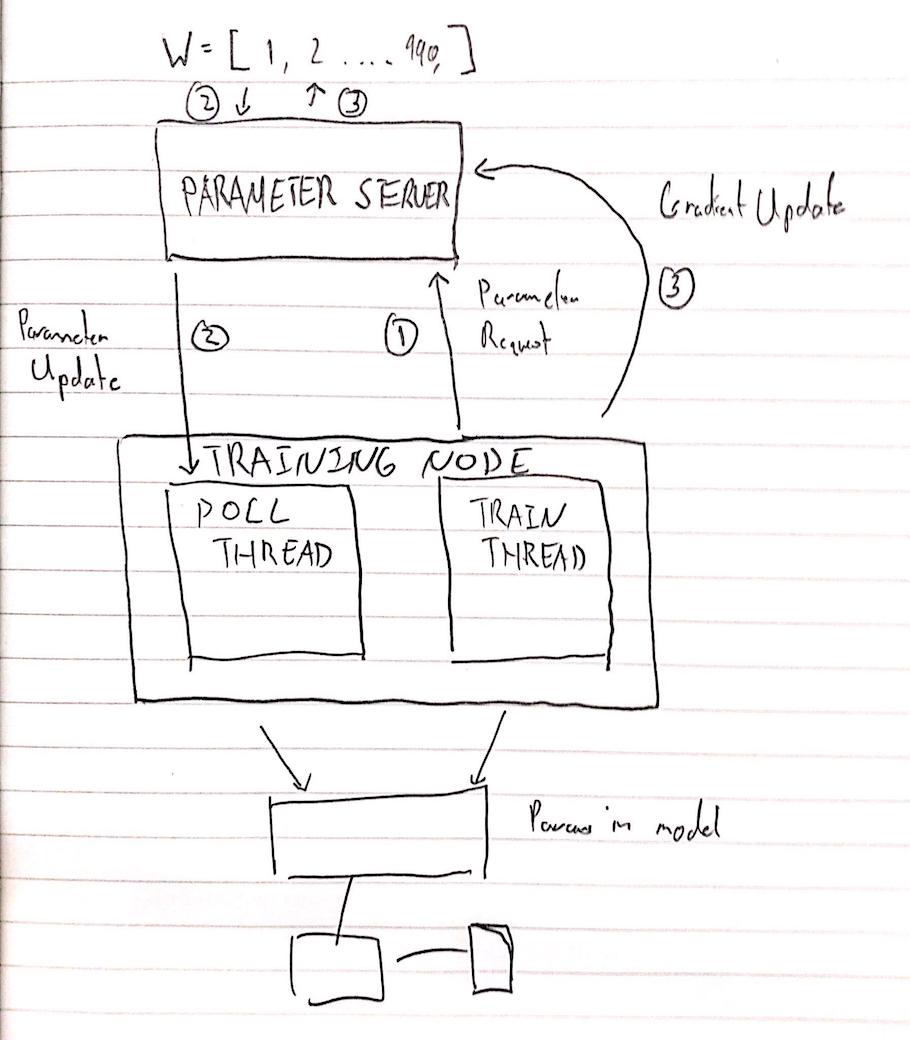

We settled on three message types and this structure:

ParameterRequest– A request for parametersGradientUpdate– A gradient update to applyParameterUpdate– A copy of the latest parameters

Here 2 and 3 should happen concurrently.

Parameter Server

There are two messages that the parameter server handles:

ParameterRequest, which has a dummy payload – this is simply a request for parameters. When the server receives this message, it will send aParameterUpdatemessage back to the requester.GradientUpdate, in which case the payload is a gradient update. In this case, we simply apply the gradient update.

The parameter server stores the model parameters in their squashed form, which makes processing these two messages pretty simple.

Training node

Our training node consists of two threads, the training thread and the listener thread.

The listener thread extends MessageListener, like the parameter server, however it only takes a single message ParameterUpdate.

ParameterUpdatewill set the params to the model (which is shared between these two threads) to the payload of the message passed in.

The training thread is the native PyTorch entrypoint, and is almost exactly identical, except it will occasionally send either a GradientUpdate or a ParameterRequest to the parameter server.

- Once every \(N_{pull}\) times, we pull the parameters. We do this by asynchronously issuing a

ParameterRequestmessage to the parameter server. Once the server receives this request, it will send aParameterUpdatewhich the listener thread will then use to update the model params. While we are pulling params, we continue training as usual. - Once every \(N_{push}\) times, we issue a

GradientUpdatemessage, sending our accumulated gradients to the server. We then zero out our accumulated grads.

Here you can see a big downside of our implementation: a ParameterRequest is the same size as a GradientUpdate, but a ParameterRequest does not need to be that large. We waste some communication overhead by sending a large tensor we do not process.

This is a shame, but we couldn’t figure out a clean way around this, so it’s just something to keep in mind for now.

Prototype Results

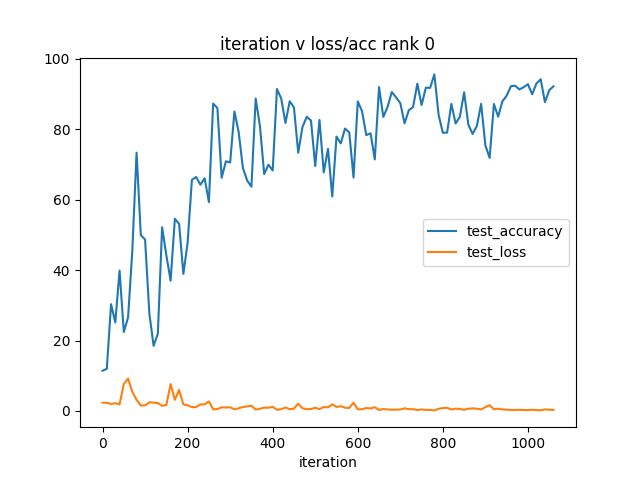

With this, we had a simple prototype. At this we were primarily concerned that we would be able to train a deep neural network, and weren’t sweating about performance. To test our code we trained LeNet on MNIST, and plotted the test accuracy/loss.

It’s an ugly graph, but training accuracy clearly rises. At this point we were satisfied with our design and focused on optimizing our prototype.

Benchmarking and Improving

The first thing we did was refactor the project to follow a more consistent project structure.

We moved everything into their respective places and broke up a single massive utils.py file.

Extending Pytorch

Next, we looked at implementing DownpourSGD as a PyTorch optimizer. It turns out there is a base Optimizer class natively in PyTorch.

This class really only has two methods, __init__() and step(). We started by copying the native SGD code and then added in DistBelief support.

def __init__(self, params, lr=required, n_pull=required, n_push=required, model=required):

# some default initialization and the like

self.model = model

self.accumulated_gradients = torch.zeros(ravel_model_params(model).size())

self.n_pull = n_pull

self.n_push = n_push

# counter for how many times we have ran

self.idx = 0

# start the DownpourListener in a separate thread

listener = DownpourListener(self.model)

listener.start()

# invoke superclass constructor

super(DownpourSGD, self).__init__(params, defaults)

We extend __init__() by letting it take in a model definition as an argument, as well as the list of parameters.

We need this in order to start our DownpourListener, which we do in a separate thread in our optimizer constructor.

def step(self, closure=None):

# send parameter request every N iterations

if self.idx % self.n_pull== 0:

send_message(MessageCode.ParameterRequest, self.accumulated_gradients) # dummy val

#get the lr

lr = self.param_groups[0]['lr']

# keep track of accumulated gradients so that we can send

gradients = ravel_model_params(self.model, grads=True)

self.accumulated_gradients.add_(-lr, gradients)

# send gradient update every N iterations

if self.idx % self.n_push== 0:

send_message(MessageCode.GradientUpdate, self.accumulated_gradients) # send gradients to the server

self.accumulated_gradients.zero_()

# internal sgd update

internal_sgd_update()

Each time we take a step, we see if we have hit \(N_{pull}\) and if so, issue a ParameterRequest to the server. Since we send messages using isend, we continue as normal. Once the server has processed the message, it will issue a ParameterUpdate, which will get picked up by the DownpourListener and update the model params.

We also accumulated our grads until we hit \(N_{push}\) upon which we send a GradientUpdate message to the server.

This allows us to use DistBelief very simply, by just changing the optimizer used.

from distbelief.optim import DownpourSGD

optimizer = DownpourSGD(net.parameters(), lr=0.001, freq=50, model=net)

That actually was very helpful, as we were able to pull down any arbitrary model and train it with minimal modification. We ended up pulling an AlexNet model definition and some CIFAR10 benchmarking code to benchmark our code.

Iterating on our prototype

Our testing setup consisted of 4 AWS c4.xlarge systems.

Our first shot

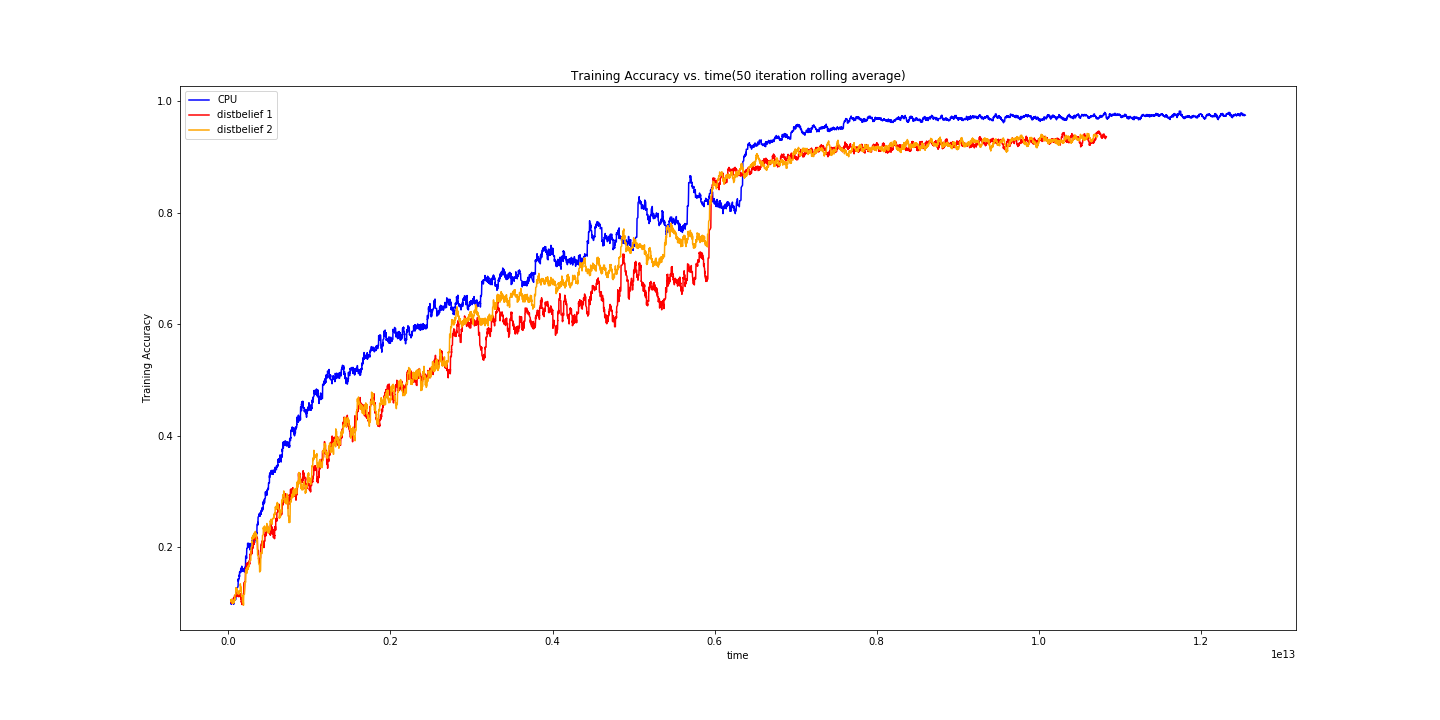

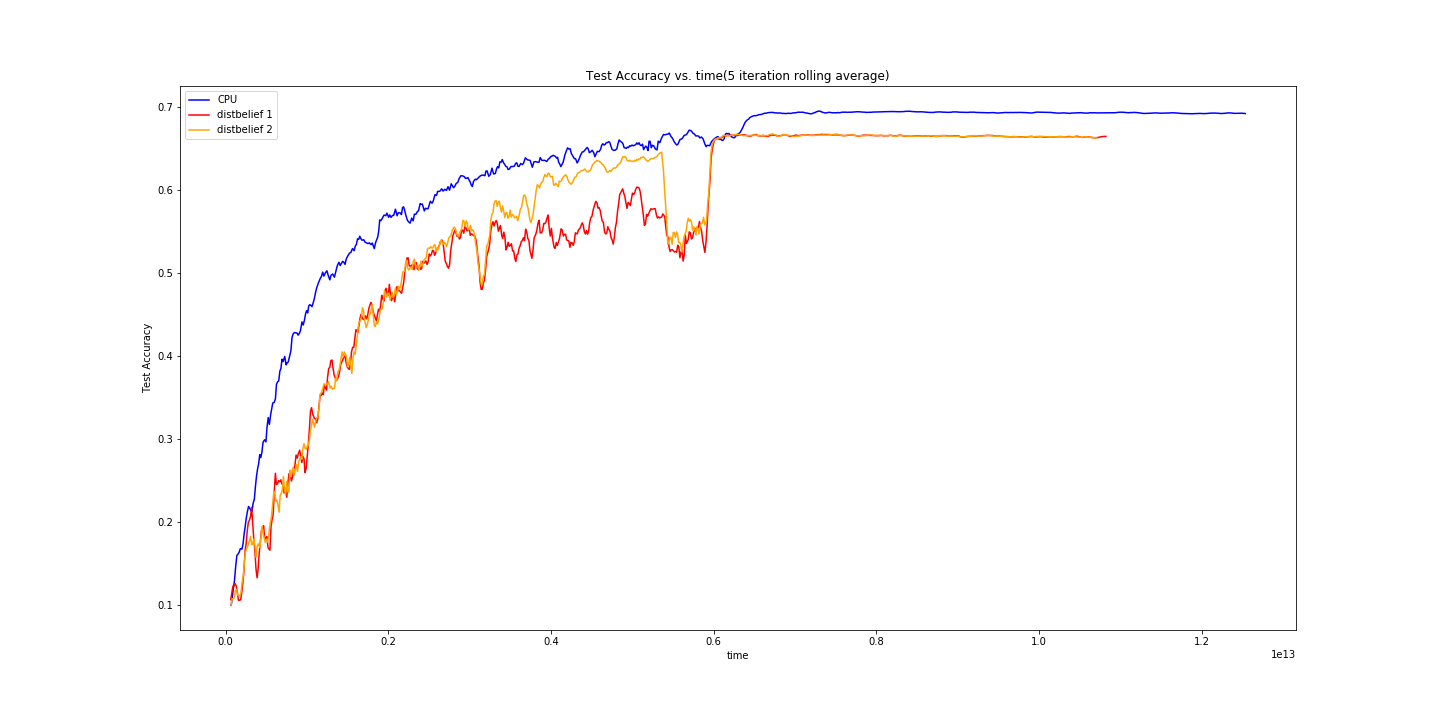

For our initial run, we trained for 20 epochs with a batch size of 64 and a learning rate of 0.1 (for single node) and 0.05 (for the distributed node). \(N_{pull}\) and \(N_{push}\) were both set to 10.

We were a little concerned here - it looked like our implementation was suffering. We took this time to explore a bit more, and eventually found this paper analyzing the delayed gradient problem.

The delayed gradient problem exists because a node may be running gradient descent on a set of parameters that is “stale”. In this case, the gradients it produces may just add noise and not contribute to lowering the training loss.

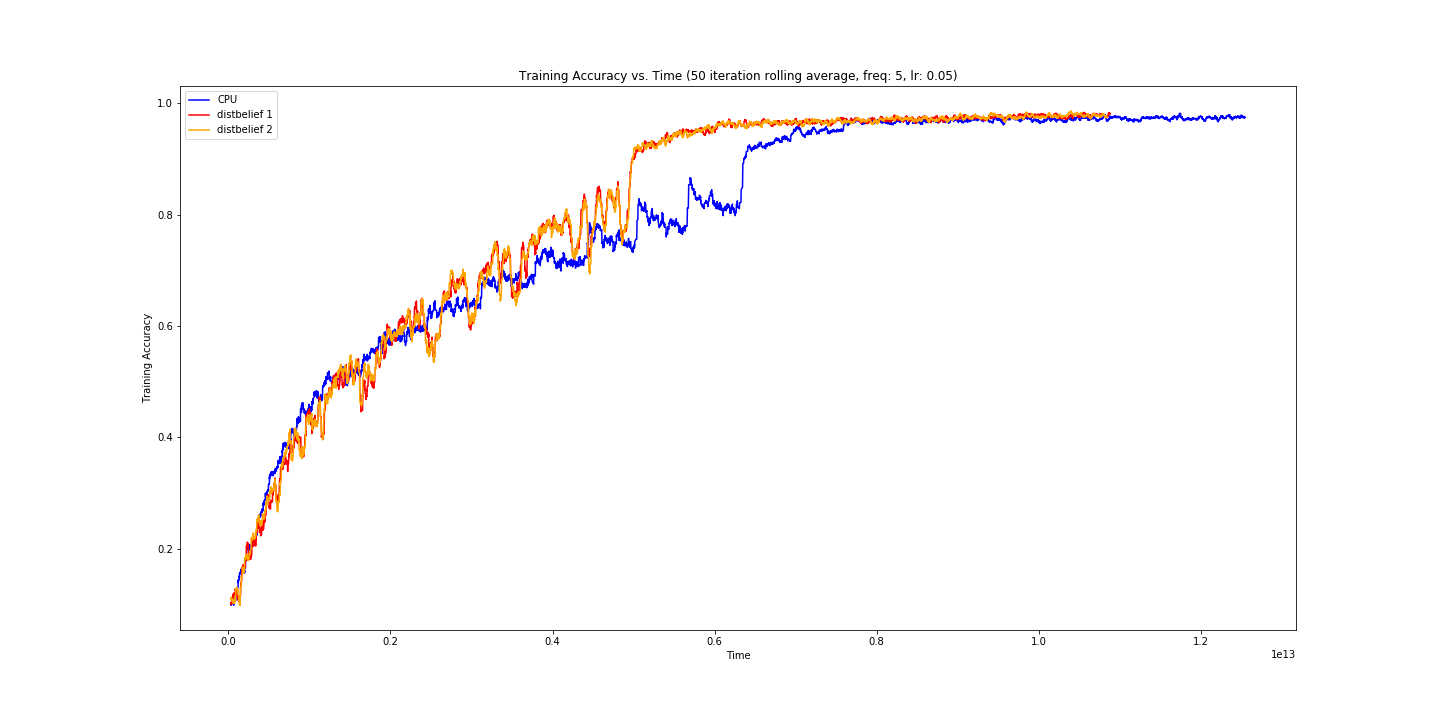

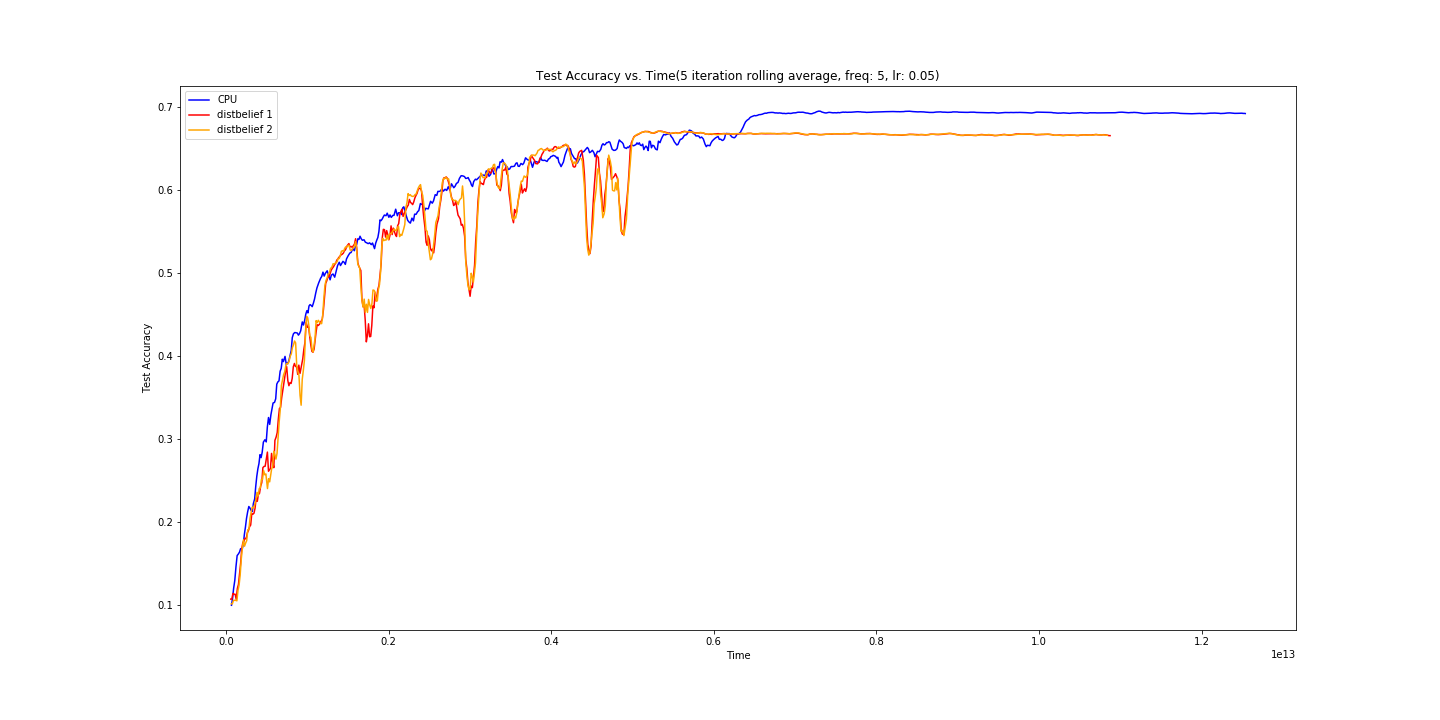

It seemed that there was a much better chance at convergence at smaller frequencies, so we dropped \(N_{pull}\) and \(N_{push}\) to 5. It was previously set to ten as we were testing by running all 3 processes on a single machine, and the training nodes would rob the server process of resources, causing it to not be able to process messages fast enough.

Dropping \(N_{pull}\) and \(N_{push}\) helps mitigate the delayed gradient problem by keeping parameters fresher, at the cost of more communication overhead.

Adjusting update frequency

Dropping the push/pull frequency had a immediate effect on our learning curve.

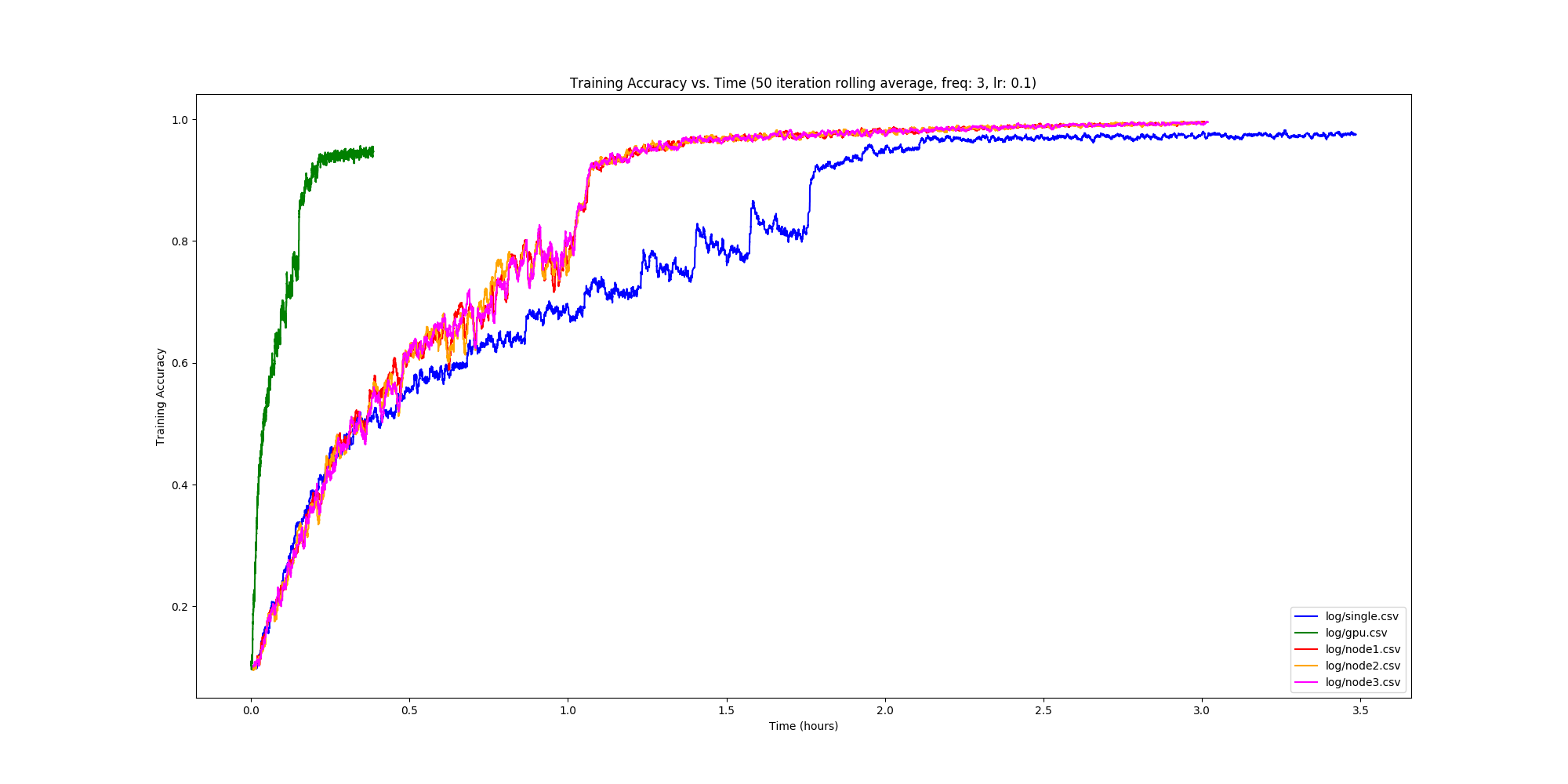

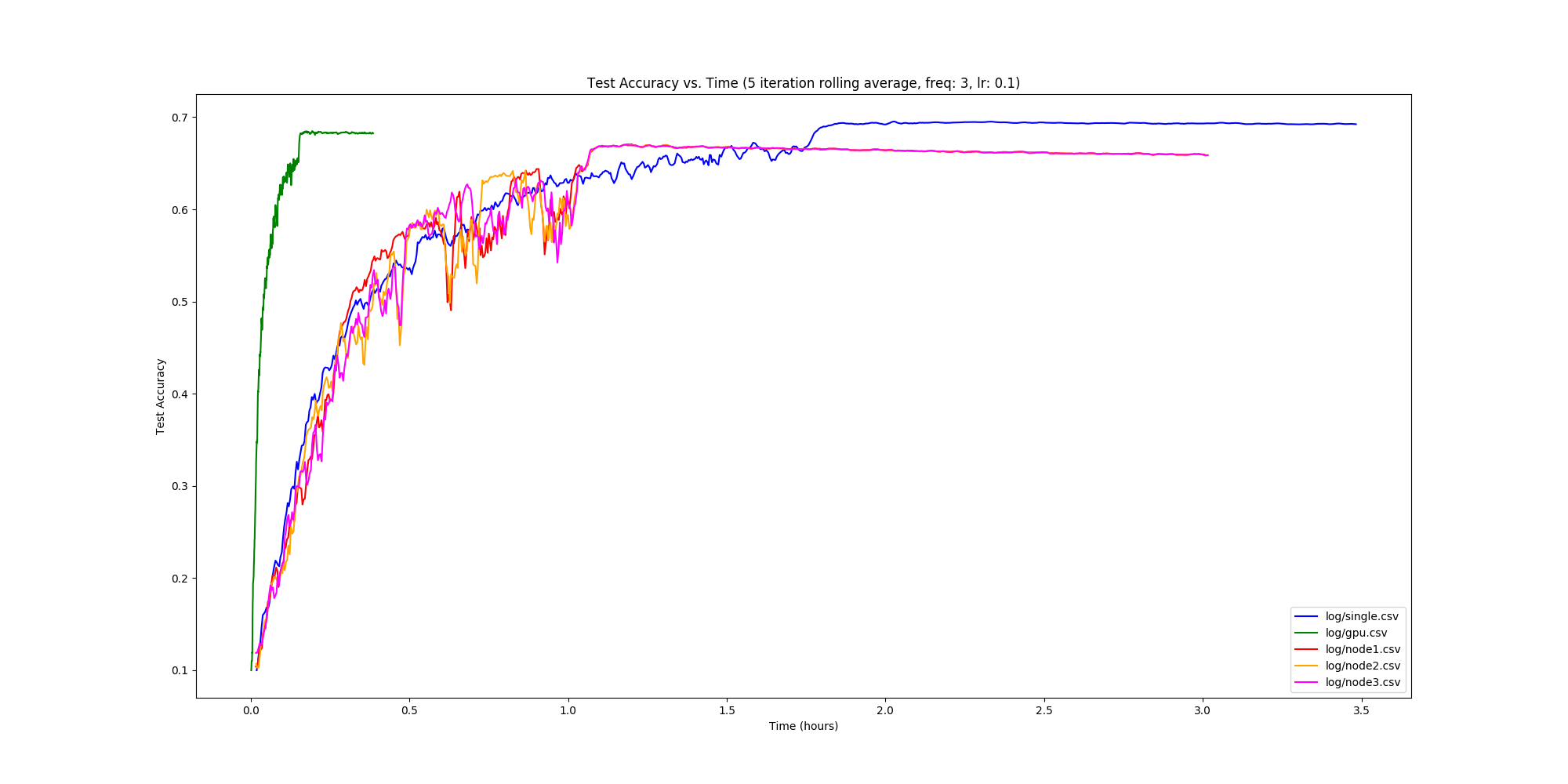

Once we got here we were very excited. Our training accuracy for out distributed 2 node approach shaved ~30 minutes off of our training time! At this point we figured a good next step would be to compare performance for our 2 node approach to our 3 node approach, as well as compare training time on a GPU (GTX 1060) as well.

Final Results

So it turns out GPUs are fast, but we’re faster than single node CPU training though by roughly an hour! What’s more than that – we’re faster than a 2-node distributed approach, which bodes well for the scalability of our system. This is great, as initially we were very concerned about the communication overhead. It seems like this wasn’t too big of a problem thankfully, which was slightly unexpected as we’re using TCP to send the tensors back and forth.

Conclusion and Future Improvements

This project was a blast to work on, and I was pretty suprised with what we were able to achieve in the end. Huge thanks to Rohan Varma, I was constantly bouncing questions and theories off of him when we were implementing this.

Some future improvements that we’ve been considering:

- sharding the parameter server

- using OpenMPI as a backend instead of TCP

- using a different strategy to push the gradients (we were thinking of pushing the gradients once they hit a norm threshold)

- implementing SandblasterLBFGS

- Taylor series approximation to help mitigate the delayed gradient problem, as seen here.