Building $\mathbb{Q}$ visually

04 Apr 2019 | theory mathematicsI’m going to go over how to construct $\mathbb{Q}$, or the rational numbers.

We’re going to start by constructing the natural numbers, and from there we’ll construct the integers, and from the integers the rationals. Our goal here is to be able to perform arithmetic in the rationals - adding, multiplying, subtracting, and dividing numbers together in the way we expect.

The original idea for this post was to go from set theory to the real numbers, but it was getting too long, so I decided to shorten it to just the rationals. I might write another post later on about constructing the real numbers.

I’m going to assume that the reader is familiar with first order logic ( $\forall, \exists$ ) and basic set theory ( set-builder notation, Cartesian product, $\cup, \cap, \setminus$ ).

Recall that a relation between two sets, $A$ and $B$ is a subset of the Cartesian product of those two sets $A \times B$.

A relation $\sim$ is an equivalence relation on a set $A$ if it is

- reflexive- $\forall a \in A : a \sim a$

- symmetric- $\forall a, b \in A : a \sim b \implies b \sim a$

- transitive- $\forall a,b ,c \in A: (a \sim b \land b \sim c ) \implies a \sim c$

The equivalence class of $a$, denoted $[a] = \{ b \in A :a \sim b \}$.

Note that the equivalence class of any object inside that class is the same- $\forall x \in [a]: [x] = [a]$.

The Naturals: $\mathbb{N}$

Let’s get started with the natural numbers. Unfortunately this part isn’t very visual, but it gets better later on.

The naturals are defined by a 3-tuple $(\mathbb{N}, 0, S)$ that satisfies the 5 Peanno Axioms.

- $\mathbb{N}$ is a set and $0 \in \mathbb{N}$

- $S : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}$ is a function with $Dom(S) = \mathbb{N}$

- $\forall n \in \mathbb{N}: S(n) \neq 0$

- $\forall n, m \in \mathbb{N}: S(n) = S(m) \implies n = m $

- $\forall A \subset \mathbb{N}: 0 \in A \land S(A) \subset A \implies A = \mathbb{N}$

Axioms 1 and 2 just define the objects in the tuple, while Axioms 3 and 4 ensure that the naturals are not too small.

Axiom 5 (also known as the induction principle) on the other hand ensures that the naturals are not too large, along with a multitude of other useful facts. It’s also the basis behind proof by induction.

If $N = $the smallest set containing $0$ and closed under $S(n) = n \cup \{ n \}$ then one such tuple can be $(N, \emptyset, S)$.

The first four natural numbers are then defined as follows:

\[0 = \emptyset\] \[1 = S(0) = \{ \emptyset \}\] \[2 = S(S(0)) = S(1) = \{ \emptyset, \{ \emptyset\} \}\] \[3 = S(S(S(0))) = S(2)= \{ \emptyset, \{ \emptyset \}, \{ \emptyset, \{ \emptyset\} \} \}\]Many people learn about the naturals without the element $0$, starting at $1$, but this makes no meaningful difference. We’ll start with $0$, as that makes our future work easier.

Arithmetic on the naturals

With this, we can define some of the operations we are familiar with, starting with addition.

- $\forall m \in \mathbb{N} : m+0 = m $

- $\forall m, n \in \mathbb{N} : m + S(n) = S(m+n)$

In addition we define $1 = S(0)$ so that $\forall m \in \mathbb{N}: S(m) = m+1$.

Let’s add two numbers to get a better sense of our construction.

\[2 + 1\]Using the fact that $1 = S(0)$ we get

\[2+1 = 2 + S(0)\]Applying our definition of addition (2) yields

\[2+1 = S(2+0)\]Now we apply case (1) to get $2 + 0 = 2$ so

\[2+1 = S(2) = 3\]And this meets our intuitive expectation that $2+1=3$.

We can also define multiplication in the naturals similarly.

- $\forall m \in \mathbb{N} : 0 \cdot m = 0 $

- $\forall m, n \in \mathbb{N} : S(n) \cdot m = n \cdot m + n$

Aside from operating as expected on naturals, these operations also uphold the properties that we expect of them - they are distributive, commutative, associative, etc.

Defining a well-ordering

We can also impose an ordering by defining the $\leq$ relation as follows:

\[\forall m, n \in \mathbb{N}: m \leq n \iff \exists r \in \mathbb{N} : n = m + r\]This gives us the basics for a subtraction operation, by denoting $r$ the difference of $n-m$

\[\forall m, n \in \mathbb{N}: (\exists r \in \mathbb{N}: m+r = n ) \implies r = n-m\]But here we run into a problem, as this operation is only defined if $n < m$. To get around this, we’ll expand $\mathbb{N}$ to $\mathbb{Z}$.

The main takeaway here is that we have $\mathbb{N}$ along with addition and multiplication operators defined over $\mathbb{N}$.

We also have a somewhat intuitive subtraction operation that enables us to solve the equation $y = a + b$ given $y, b$, but it fails for $y \leq b$.

This gives us some algebraic motivation for constructing the integers, so that $\forall y, a,b \in \mathbb{Z}: y = a + b$ has a solution given $y, b$.

The Integers $\mathbb{Z}$

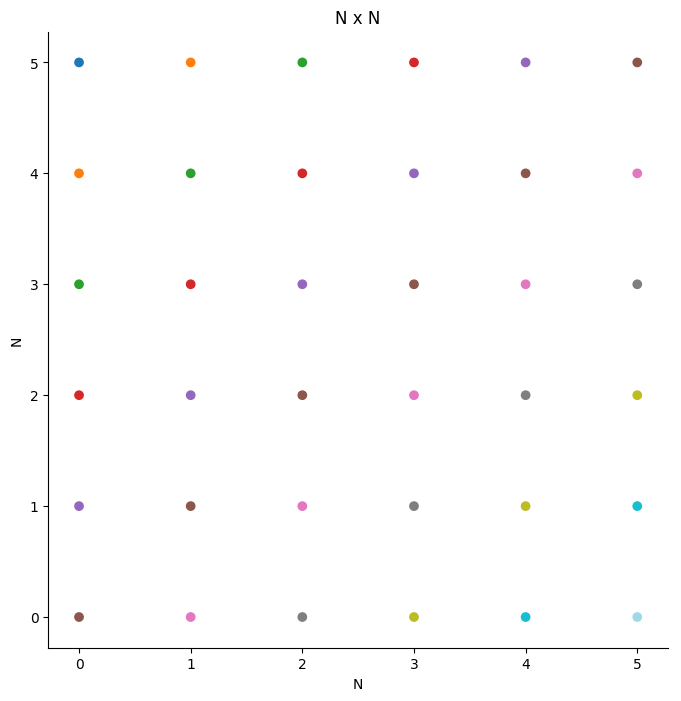

To construct $\mathbb{Z}$, we will consider all pairs of naturals numbers, or $\mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N}$.

We’ll define an equivalence relation $R$ over all pairs of pairs, $(\mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N}) \times (\mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N})$ such that

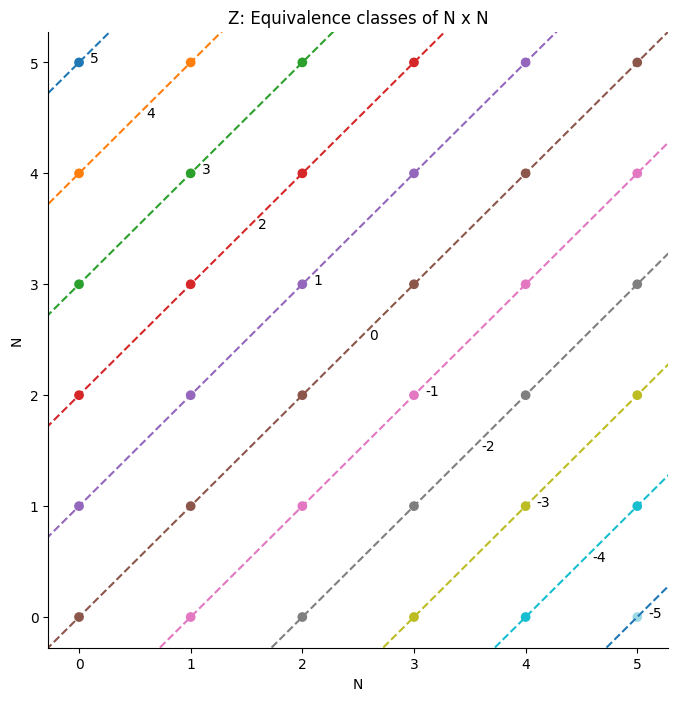

\[\forall (p_1, q_1), (p_2, q_2) \in \mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N}: (p_1, q_1)\ R \ (p_2, q_2) \iff p_1 + q_2 = p_2 + q_1\]The set of all equivalence classes gives us a way to partition $\mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N}$ and is in fact the integers, $\mathbb{Z} = \{ [(p, q)]: \forall p, q \in \mathbb{N} \}$

We can visualize this by plotting all pairs $(p, q) \in \mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N}$, and coloring them differently based on their equivalence class.

Note: All the axes you see should have arrows, but I couldn’t figure out how to do it properly in matplotlib.

Here each pair is colored based on each equivalence class - we can then visualize an equivalence class (integer) as the set of all points that share the same color.

You can see that each class corresponds to a line $y = x +b $ with a different $b$.

The naturals are embedded in the integers as the set $\mathbb{N} = \{ [n, 0]: \forall n \in \mathbb{N} \}$

Arithmetic on the integers

Let’s define the unary negation operator, as well as addition, subtraction, and multiplication as follows.

- $-[(p,q)] = [(q, p)]$

- $[(p_1,q_1)] + [(p_2, q_2)] = [(p_1 + p_2 , q_1 + q_2)]$

- $[(p_1,q_1)] - [(p_2, q_2)] = [(p_1 + q_2 , q_1 + p_2)]$

- $[(p_1,q_1)] \cdot [(p_2, q_2)] = [(p_1 \cdot p_2 + q_1 \cdot q_2, p_1 \cdot q_2 + p_2 \cdot q_1)]$

To get a better sense of arithmetic in $\mathbb{Z}$, let’s try to visualize how $1+ -2 = -1 = 2 - 3$.

Going back to our construction, each integer is an equivalence class so it is a subset of $\mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N}$.

We can pick some element from this subset to represent the entire equivalence class. So we pick some pairs $(0, 1), (2, 0), (0, 3), (1,3)$ to represent $1, -2, 3, 2$ respectively, since they will have the same equivalence class.

If we add together $1 + -2 = (0, 1) + (2, 0)$, we get a new vector, $(2, 1)$, whose equivalence class is the same as the integer result ($-1$). Since addition over $\mathbb{Z}$ is defined as vector addition, adding the vector representations of integers yields a vector representation of the sum.

We can see also that the pair returned by the subtracting $3-2 = (0, 3) - (1,3) =(0+3, 1+3) = (3,4)$ is in the same equivalence class, and therefore is the same color.

One thing to note here is that addition and subtraction works as expected regardless of the pair we choose to represent the equivalence class.

So now we’ve solved the problem described at the start of this as $\forall m, n \in \mathbb{Z}. \exists r \in \mathbb{Z} : r = m -n $ and now have a well-defined subtraction.

Note that we’ve been careful about only using properties that we’ve previously defined (addition and multiplication on $\mathbb{N}$ only).

But there’s still another problem, because a similar problem exists for equations of the form $ y = a \cdot b $.

We’ll solve this by using a similar technique as before to expand $\mathbb{Z}$ to $\mathbb{Q}$.

The Rationals $\mathbb{Q}$

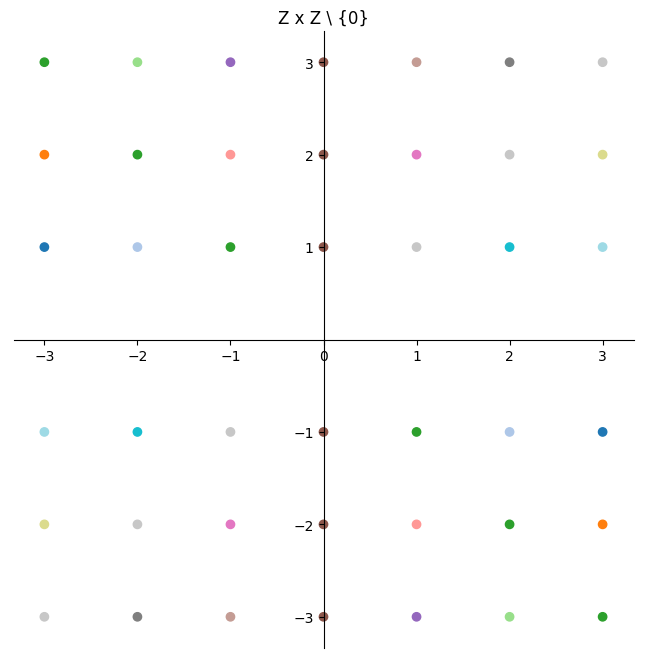

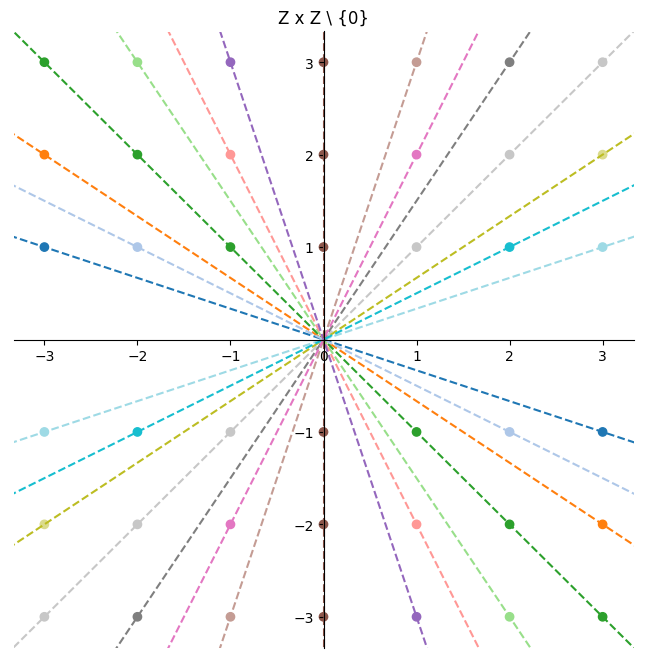

We will define a relation $R$ on $\mathbb{Z} \times \mathbb{Z} \setminus \{0\}$ such that

\[\forall (p_1, q_1), (p_2, q_2) \in \mathbb{Z} \times \mathbb{Z} \setminus \{0\} : (p_1, q_1)\ R \ (p_2, q_2) \iff p_1 \cdot q_2 = p_2 \cdot q_1\]We can use the same idea to visualize the equivalence classes,

The equivalence classes are a bit harder to see here, but again they correspond to lines, just now with different slopes instead of intercepts.

Each pair in $\mathbb{Z} \times \mathbb{Z} \setminus \{0\}$ corresponds to the rational number $\frac{p}{q}$. Note that the integers are represented inside the rationals as the set $\{(p, 1) : \forall p \in \mathbb{Z} \}$

If we ignore the case when $p=0$ we can see that there’s an inverse relationship between the slope $m = \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} = \frac{q - 0}{p - 0} = \frac{q}{p}$ and the rational number $\frac{p}{q}$ so $y = mx$ gives the equivalence class that represents the rational $\frac{1}{m}$.

Arithmetic on the rationals

Now let’s consider arithmetic over $\mathbb{Q}$ by defining the operation of addition, subtraction multiplication and division as follows:

- $[(p_1,q_1)] + [(p_2, q_2)] = [(p_1 \cdot q_2 + p_2 \cdot q_1, q_1 \cdot q_2)]$

- $[(p_1,q_1)] - [(p_2, q_2)] = [(p_1 \cdot q_2 - p_2 \cdot q_1, q_1 \cdot q_2)]$

- $[(p_1,q_1)] \cdot [(p_2, q_2)] = [(p_1 \cdot p_2 , q_1 \cdot q_2)]$

- $[(p_1,q_1)] \div [(p_2, q_2)] = [(p_1 \cdot q_2 , q_1 \cdot p_2)]$

Again let’s try to visualize some simple arithmetic ($-3 \div 2 = -1 + -\frac{1}{2}$) in $\mathbb{Q}$ to get a better sense of our operations.

We’ll pick the pairs $(-3, 1), (2, 1), (-1, 1), (1, -2)$ to represent $-3, 2, -1, -\frac{1}{2}$ respectively.

We can see that $-3 \div 2 = (-3 \cdot 1, 1 \cdot 2) = (-3, 2)$ and that $-1 + -\frac{1}{2} = (-1 \cdot -2 + 1 \cdot 1, -2 \cdot 1) = (3, -2)$.

When plotted these we can see that these two vectors share the same slope and thus represent the same rational number.

And now we’re done - we have the rational number system, $\mathbb{Q}$, as well as the normal arithmetic operations that we learned in grade school.

We’ve built from set theory by defining progressively more complicated number systems, working our way from $\mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Q}$.

References

I learned most of this in MATH 131 taught by Professor Biskup. More details about the construction, as well as proofs of many of the properties I glossed over can be found on the course webpage here.

I used matplotlib to make these visualizations, the code can be found here if you’re interested.

If you spot any mistakes/inaccuracies please let me know or better yet make a PR.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Set-theoretic_definition_of_natural_numbers